Device Selection: When to Choose a Midline versus a PICC

By Nancy Moureau, PhD, RN, CRNI, CPUI, VA-BC

One of the most common clinical questions I encounter is, when is it appropriate to choose a Midline versus a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC)? This question requires consideration for peripheral or central access, determination of risk, and evaluation of the treatment type, duration, and future needs of the patient. We know that peripheral intravenous catheter (PIV) insertions are the mainstay for delivering acute care medication infusions, with the vast majority of patients receiving a PIV immediately upon admission. Whenever possible, central catheter insertions, even PICCs, are avoided to sidestep the issue of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI). However, Midline catheter insertions are another story.

What is a Midline Catheter?

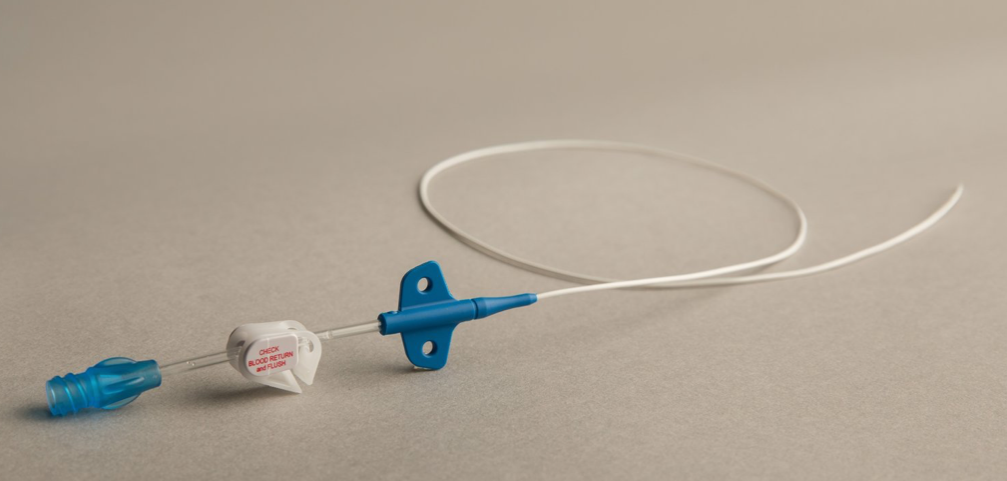

First, let us define a Midline catheter. While there are many different types of Midline catheters, as determined by the Infusion Nurses Society as an intravenous (IV) catheter inserted through a peripheral vein of the upper arm via the basilic, cephalic, or brachial veins with the terminal tip located at the level of the axilla for children and adults (Gorski, et al., 2021). In addition, scalp veins and veins of the lower extremities are optional locations for Midline catheters in neonatal patients. Midline catheters may have different lengths and configurations, allowing Seldinger, Modified Seldinger, and Accelerated Seldinger insertion methods. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (O’Grady et al., 2011), Midline catheters should be selected based on the intended purpose and duration of use, known complications, and experience of individual catheter inserters.

Midline catheters are a type of peripheral catheter, longer than short PIVs, and indicated for patients requiring therapy for more than five days but less than a few weeks (Gorski et al., 2021; Chopra et al., 2015). Generally, 8-25cm long, Midline catheters are inserted with ultrasound guidance into the larger diameter veins of the upper arm and tend to last longer than a PIV. The CDC states to use a Midline catheter or PICC instead of a short peripheral catheter if the duration of IV therapy will likely exceed six days (O’Grady et al., 2011). Central venous catheters, such as PICCs, and the associated risk of infection should be avoided if the medications included in the treatment plan are not irritating and do not require a duration that exceeds four weeks. Midline catheters typically do not last without complications for more than a few weeks but can provide patients with a longer, more reliable access alternative to the short PIV. According to the CDC, Midline catheters are replaced only when there is a specific indication for removal, such as a complication or completion of therapy (O’Grady, 2011).

The Access Vascular HydroMID catheter has demonstrated 6X fewer complications than a standard polyurethane catheter in a retrospective clinical study. Click here to learn more.

Selecting a Midline Catheter

Midlines are an excellent option for patients when their medications and solutions are generally isotonic and non-irritating. Geriatric and pediatric patients can benefit from Midline catheters as a more reliable form of vascular access that will not fail as often as a PIV. When a PIV fails in less than 24 hours, Midline or PICC may be better options. Any patient requiring IV infusions for more than a few days may benefit from a Midline catheter. Catheter choice based on the estimated duration of treatment typically guides selection. However, factors for insertion location, catheter material, ease of insertion, reliability of IV access, and comfort for the patient are considerations for the type of catheter that is best suited for the patient (Gorski, 2021).

Consideration for the placement of a Midline catheter requires the clinician to take the next step to fully evaluate the patient’s needs and establish intravenous (IV) access in a reliable form. Often the first choice is speed and convenience for catheter selection and insertion. The first choice for the emergency department is the PIV; the most common insertion location is the antecubital fossa. Helm, in 2015, noted that one out of every two PIV catheters would fail before the end of treatment (Helm et al., 2015). Thus, PIVs are not a reliable form of access for patients who require more than a few days of treatment. A Midline catheter can provide longer dwell time and may allow the patient to complete therapy without catheter replacement. Midline catheters do have complications resulting in catheter failure from occlusion, dislodgment, and thrombosis. However, the longer, softer catheter generally achieves much better dwell times than short peripheral or ultrasound-guided longer peripheral catheters. The Midline option promotes vein preservation by using fewer catheters and insertion attempts while being more cost-effective than a central catheter. The use of Midline catheters is consistent with the principles of Vessel Health and Preservation.

The popularity of Midline catheters is increasing related to low cost, ease of insertion, and lower risk of infection. Current research indicates varying safety levels for the administration of intravenous irritating medications, such as vasopressors, through PIVs and Midline catheters (Prasanna, 2021). This new research opens the door to expanded use of PIV and Midline catheters for vesicant medications but stresses the need for close observation and assessment during infusion. In addition, new research on catheter materials for hydrophilic catheters that have a lower incidence of occlusion and thrombosis may pave the way to longer dwell times with fewer Midline catheter complications (Bunch 2022). The method of complication reduction for CLABSIs, thrombosis, and occlusions rests on the avoidance of cellular attachment on the well-hydrated hydrophilic surface of the catheter. These newer materials are also available for PICCs and may help to level the playing field between Midlines and PICCs in reducing the risk of complications.

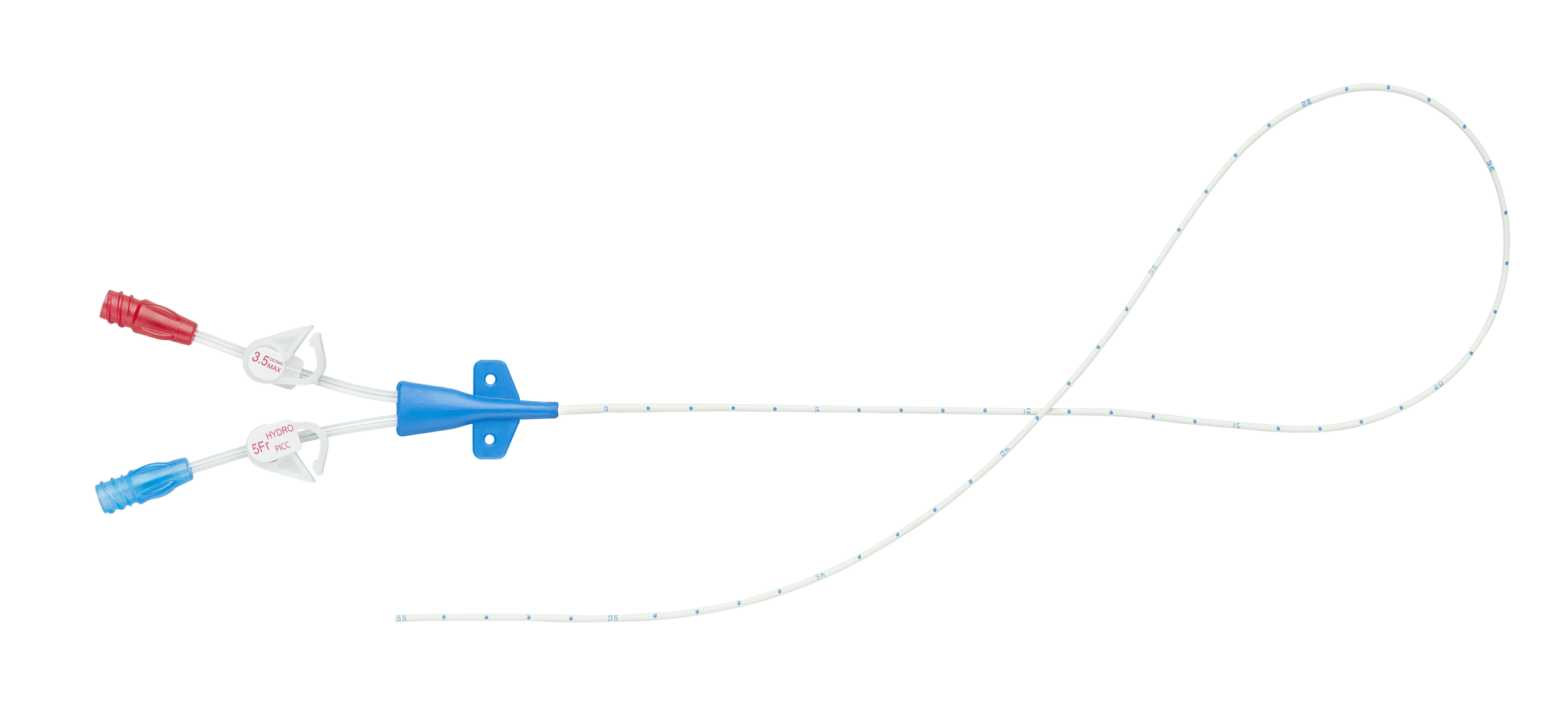

When to Select a PICC

The major risk issues with PICCs focus on the two most serious complications of infection and thrombosis. These two complications contribute to higher costs, lost hospital revenue, morbidity, and mortality of patients. To adequately protect patients, central venous access placement requires treatment or duration that indicates a need for central infusions. In the past decade, PICCs have gone from the most commonly ordered and convenient IV device to more careful consideration as CLABSIs began to impact hospitals. Often orders for PICCs were precipitated by the inability to gain PIV access. As technology and ultrasound use with IV devices have expanded, more options for ultrasound-guided PIV and Midline placement have become more favorable. Chopra, in 2015, released an evidence-based consensus on PICC appropriateness termed MAGIC (Chopra et al., 2015). The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravascular Catheters (MAGIC) listed indications for PICCs, central venous access devices, Midlines, and ultrasound-guided peripheral catheters. While clinician judgment should not be discounted, MAGIC was the first publication to list clear indications, providing simple charts and clear instructions on when to use each device. MAGIC recommendations also encouraged the use of single-lumen catheters as a means to reduce the risk of infection and other complications.

So, when is it best to use PICCs?

Indications for PICC placement, designated by MAGIC, discourage using PICCs for therapies five days or less or solely for difficult access patients, opting instead to focus on infusion requirements for longer treatment durations. Other indications for PICCs include the need for infusions of irritating or vesicant medications or solutions and frequent blood draws. Once placed, PICCs can remain as long as clinically necessary, to the end of therapy, or when complications require removal. The risk of infection is ever present for all IV devices. While PICCs have a generally higher infection rate than peripheral and midline catheters, the incidence of infection is less than or equal to all other central catheters (PICCs 0-2.1/1000 catheter days). PICCs are best used when there is a clear indication of the need for a centrally placed catheter and when trained inserters are available.

Consideration for the choice of an IV device with the lowest risk may include midline catheters and PICCs. Evaluating improved catheter materials is necessary to fully explore new options to achieve maximum complication reduction and safeguard our patients. One way to ensure risk reduction is to establish a policy for regularly scheduled education and training with a plan for competency assessment of inserters and those accessing IV devices. Using the central line bundle checklist for inserters and emphasizing disinfection practices for those who access and manage these devices can help to ensure lower infection rates for intravenous catheters. Observation and audits of dressings for adherence and scheduled dressing changes can also reduce the risk of infection with these catheters. Finally, establishing vascular access committees to identify gaps in practice that put patients at risk can lead to effective quality improvement initiatives and goes a long way toward improving outcomes with all vascular access devices. These methods can contribute to better device selection and risk reduction with these intravenous catheters that have become essential for delivering medical treatment to patients (Simonov 2015).

What if your midline and PICC catheter complication rate could be significantly reduced?

The Access Vascular HydroMID and HydroPICC have demonstrated with in vitro, in vivo, and in clinical data to significantly reduce complications like occlusions and thrombosis. Check out our data page to learn more. And contact us to have a demo of our catheters that seamlessly fit into your existing workflow.

References

Bunch J. A Retrospective Assessment of Midline Catheter Failures Focusing on Catheter Composition. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2022 Sep 1;45(5):270-8.

Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S et al. (2015) The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results from a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med 163(6 Suppl):S1–40. doi: 10.7326/M15-0744.

Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. The American journal of medicine. 2012 Aug 1;125(8):733-41.

Gorski L, Hadaway L, Hagle M, Broadhurst D, Clare S, Kleidon T, Meyer B, Nickel B, Rowley S, Sharpe E, Alexander M. (2021). Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, 8th Edition. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(suppl 1):S1-S224. https://doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396

Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JD, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: peripheral IV catheter failure. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2015 May 1;38(3):189-203.

Liem TK, Yanit KE, Moseley SE, Landry GJ, DeLoughery TG, Rumwell CA, Mitchell EL, Moneta GL. Peripherally inserted central catheter usage patterns and associated symptomatic upper extremity venous thrombosis. Journal of vascular surgery. 2012 Mar 1;55(3):761-7.

Moureau N, Chopra V. Indications for peripheral, midline, and central catheters: summary of the Michigan appropriateness guide for intravenous catheters recommendations. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access. 2016;21(3):140-8.

Moureau N, Chopra V. Making the Magic: Guiding Vascular Access Selection for Intensive Care – a Summary of MAGIC. ICU Manag Pract. 2016. https://www.improvepicc.com/uploads/5/6/5/0/56503399/icu_v16_i1-nancymoureau_cpamend_v2.pdf